My Pivot Part 1: Why Python Couldn’t Cut the Cake

Ctrl. Alt. Pivot: When I realised the problem was bigger than proteins.

“You aren’t naive or unfocused, but very brave.”

These words were from my dad a few years ago, when I was starting to lose my faith in things unfolding how I thought they would. They marked the start of my permission to pivot—or perhaps the moment I stopped feeling ashamed of being labeled a "classic ADHD job hopper".

"Every role you’ve had has been quite different in its field. Many people specialize and never dare to look out the window at other problems. The problem will always be bigger than what you are doing. That’s why they need system thinkers like us, Number 2." (I am daughter number 2 out of 4, hence the pet name.)

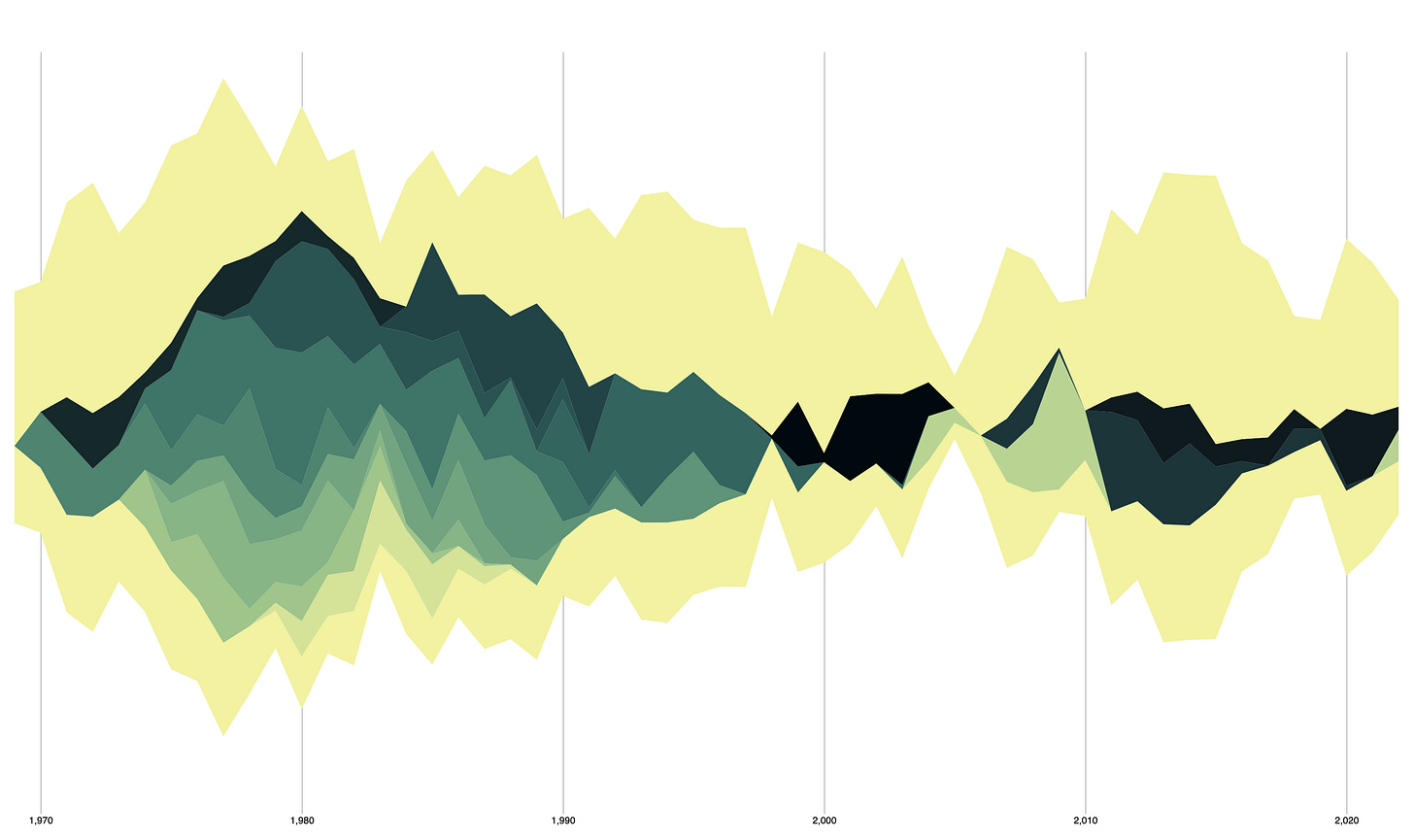

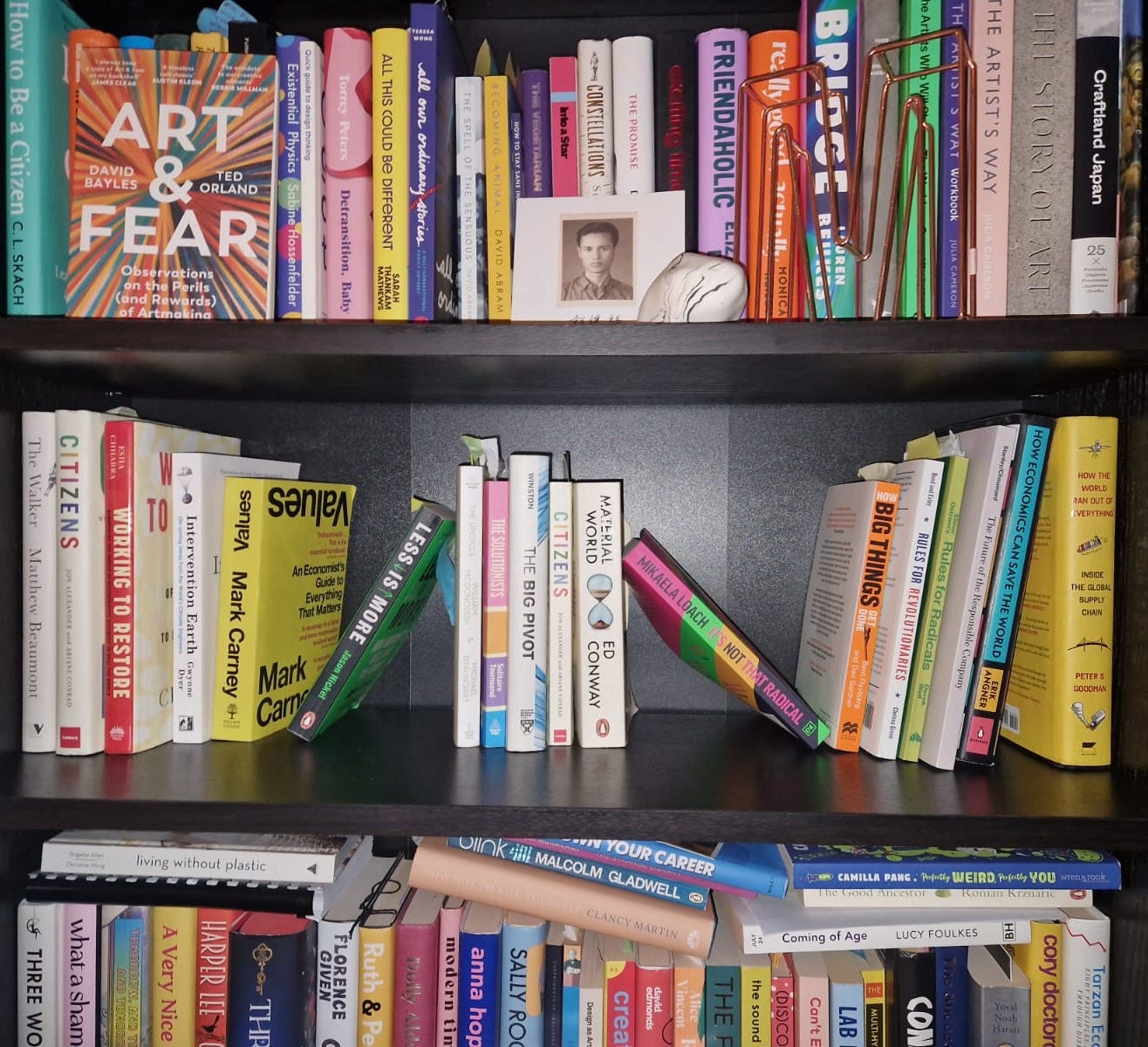

Let me tell you a bit about my pivot. Apart from the privilege of being an author, I was born and trained to be a scientist. I absolutely loved biochemistry, the language of how all the sciences come together. It's a vast field, and I wanted to try all of it because only then can you gain a bird's-eye view of how to model and intervene. I wanted to see the problem whole. I wrote to fill in the gaps my job left and ended up falling into writing because of this. I published my first book in 2020, which did very well and was a huge blessing for my writing career. 📚 However, as a scientist, I didn’t want to leave my laptop—or the years I spent learning Python—on standby.

As a neurodivergent woman of colour, working in the tech startup industry has been… interesting. My average daily gig was sitting in a room of 30 male software engineers and a handful of science queens. Perhaps my humour and PhD got me through the door, but in the room, it was a different experience. No matter how many times I wore my finance-bro gilet or said, "It’s all about the data," the plane didn’t quite land ✈️. I talk about this a lot in my latest book, ‘Breakthrough’, where shortly afterward, I asked my dad for solace:

"I love delving into things, discovering everything I can about them, becoming obsessed with every new branch of the tree I am climbing. It’s why I poured years into my PhD in my first love—biochemistry. But over time, the subject felt stale. I knew there was more to science than this: data to be grabbed and new worlds to build with it, Minecraft-style. So, after completing my doctorate, I threw myself just as obsessively into machine learning research, brute-forced my way through a Python course, and built a career as a bioinformatician. Welcome to my first existential crisis, where, at one particularly low point, I nearly bought a high-tech mechanical keyboard to embody the mind of a software engineer."

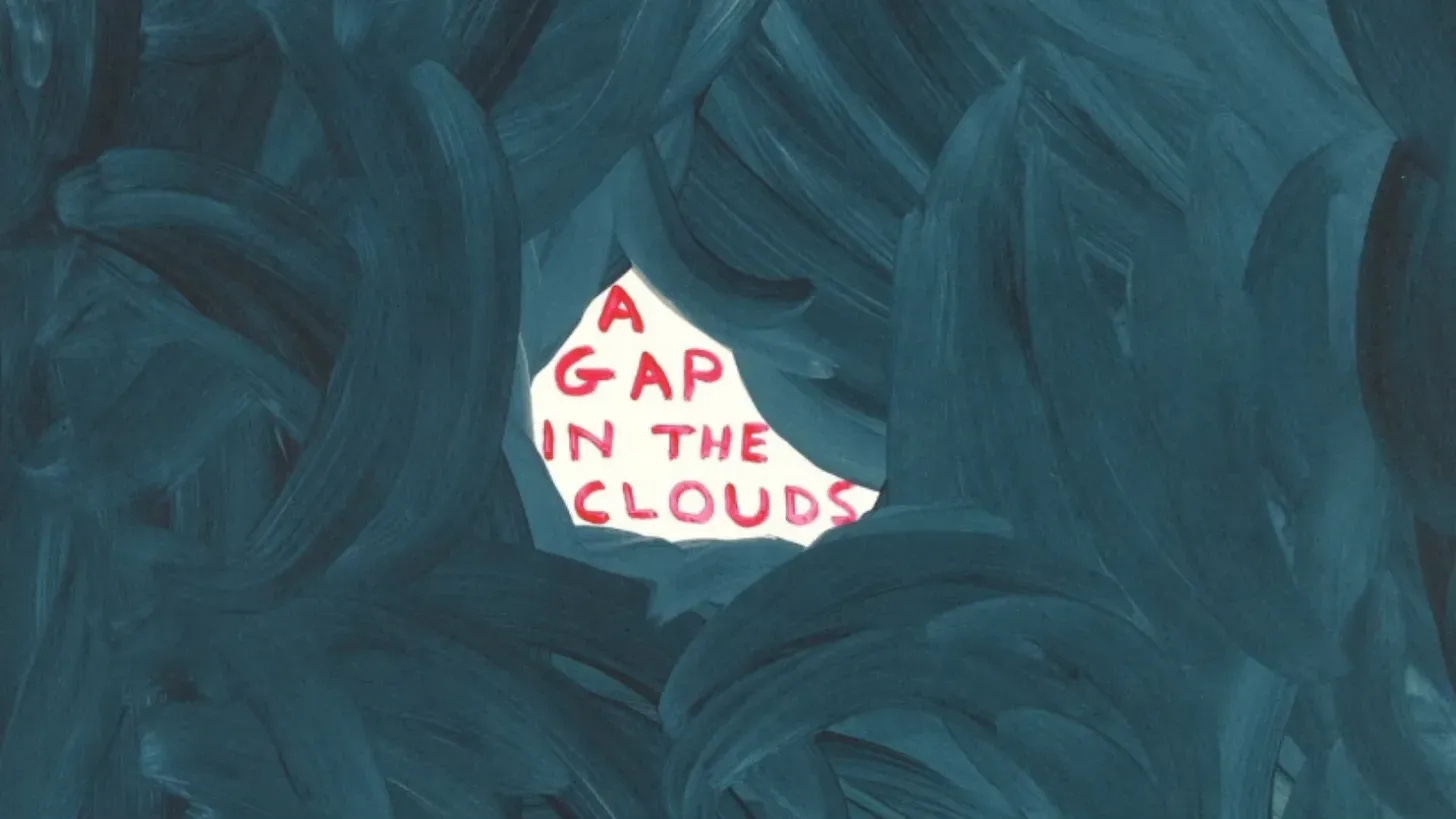

I’ve had many types of roles as a scientist—wet lab (coat and goggles👩🏽🔬 ) and dry lab (computers and gilets 👩🏽💻)—switching between modeling single proteins and vast biological networks. Most people specialize in one or the other, but I wanted to see it all, which is why I chose bioinformatics. Despite my wanderlust for the elements, I often felt a perpetual anxiety that the wide net I had cast still wasn’t big enough. There was a sticky inertia—a heartbreak—tied to the problems that sang in my mind like birds on balconies, waiting 🦅. Each idea perched there, fluttering, while I struggled to find a way to explain it. Everything I wanted to say or solve always seemed to drift outside the scope of the work we were doing. Over time, this dissonance grew until, eventually, I no longer wanted to say anything at all.

I loved my last job. The people were great, the company was great, and the project felt tailor-made for me. I imagined that my balcony birds would finally have a Campari on the deck for a while 🍹. Everything about it made sense—it bridged my training and the way my mind thrives on projects with broad, expansive scope. It felt like the narrative I’d worked for had materialized: a place where I could exist between the parallel universes of biochemistry 🪐.

I found myself genuinely happy coding. Everything clicked. I developed a kind of software engineer’s confidence, donning my gilet and facing dreaded DevOps—the terrifying logistics of software development and operations. But that’s a story for another time. Minus the occasional Python bug, time flowed smoothly, like milk mixed with honey 🍯.

Halfway through, when I was finding a good rhythm, my feet began sinking into that familiar mental toffee again, tethering me while my heart and mind strained outward toward the light . No matter how hard I focused, I couldn’t code fast enough to keep pace with the problems multiplying outside . Zoning into Python, I sculpted small worlds, but progress was painfully slow—like trying to outrun a collapsing universe. That’s the thing about turning your back on the big picture: claustrophobia creeps in, and every unseen problem stares you down 👁️.

ADHD, my usual guide, should have been my compass, but this time, it tasted different.

No matter how bright my good days shone, I feel queasy saying I was solving one problem when I was inadvertently creating five more.

I knew that no matter how many nights I worked, or how well I coded, no amount of optimized proteins would make the industry sustainable.

It was as if I were pressing down on the wings of my dear balcony birds until everything went silent. I became numb, detached from my instincts.As I grew quieter, the birds only sang louder, flapping their wings, shaking my focus. The more I immersed myself in my role, the more the world outside seemed to close in with its eyes of distress. The sky blackened at midday, wildfires crept closer, and waters continued to rise 🌊. Helplessness took root, and my mind overflowed with questions:

Why are our computers still running on brown energy?

What about the AI emissions that even companies like google forgot to account for?

What about the sheer amount of chemical waste and plastic? What about the people in our supply chains—have they adopted new green practices, so that our efforts aren’t in vain?

Am I really making a difference, or is this job just part of a system that cares more about money and short-term results?

Why don’t different areas of science work together more to solve environmental problems?

Would I be more useful somewhere else—maybe in a place that focuses more on sustainability?

No matter how many times I had coded listening to ‘Flood’ by Take That, no one seemed to ‘dance the rain’ with me on this.

Perhaps I was asking the right kind of questions - but was I in the wrong role to solve them?

So, in true millennial style, I ran to a podcast 🎧—specifically I Weigh with Jameela Jamil, where Simon Sinek was being interviewed—and began my search for my ‘WHY.’ Clinging to the philosophy of my subject like a lifeline, I declared to myself that the purpose of my role was to:

Develop algorithms to optimize proteins in order to save resources and energy otherwise spent in the lab.

That’s sustainability, right?

But something about it felt off—like the knowledge of using brown energy to do this and that the best of my efforts was to be ‘less bad’, which isn’t the same as being ‘more good.’ 🌎

“How can we ensure that advancements in healthcare and medicine support human well-being without compromising the health of the planet?”

I started whispering this thought to myself every day, then every hour, until it consumed me second by second and no amount of coding alone could solve it in the time frame my mind needed. The speed and magnitude of these thoughts shattered the carefully contained problems I had tried to suppress, leaving me trapped in a burning balloon. 🎈

Ultimately, I knew the problem was bigger than what smart technologies could fix.

Just to be clear, it wasn’t to do with that fact that computational projects like mine were not making a difference, if anything they are essential to modelling scenarios and forming arguments for green technologies, not to mention help reduce waste.

It wasn’t that I didn’t believe in the work I was doing. I cared deeply about reducing waste and optimizing resources in the lab, but the tension between my eco-anxiety and the slow grind of coding began to weigh on me. I loved research, but the growing awareness of larger, systemic problems left me feeling trapped—like no matter how much I could work, it wasn’t fast or impactful enough to drive real change 🛑. I knew I had something to offer beyond the immediate scope of my job. I just didn’t know where or how to channel it yet. But staying in a role where I felt disconnected and powerless wasn’t going to help anyone—not me, the work, or the problems I wanted to solve.

TRUST ME, this isn’t something that is easy to admit after you spend the whole of your 20’s finally reaching the point of a dream job, to only then explain this to nice people who once placed their faith in you - my managers, friends, and family. I relived this moment about 1000 times, which inflated as the gaps between my code grew, until I lost my trained capabilities, instincts and faith my own judgement. The dark space between deletion and hope. I was within Autistic burnout.

Ctrl. Alt. Deleted.

I didn’t realize I had burnout until I found myself crying every morning before 10:30 a.m, often without knowing why. It wasn’t until I received a message on Instagram from Hana Walker-Brown that things started to click. She comforted me and pointed me to her Substack podcast, Late to The Party, where she described burnout as “like watching the house you built burn down right in front of you.” But this time, people were watching—and my worries became more real than ever as the news spun around the world. It didn’t just feel like a failure of all the hard years I’d spent in education. It came with a crushing guilt and a sense of powerlessness to make a real impact from where I was.

There’s an unspoken wisdom that we’re supposed to stay in our lanes—that sustainability isn’t my problem to solve 🚧. Maybe I was supposed to turn the alarm down, carry on coding, and trust that everything would somehow be okay. But I knew the problem was bigger than biochemistry, technology, or even, dare I say it, proteins. (I know. It still hurts.) As a fellow researcher and green advocate told me: "It ultimately has to be a company decision." That’s the sky lifted and where I took one of the biggest leaps of my AuDHD life—I quit the dream job 📦.

Many would probably call me a climate quitter, a worry wart, or a disturbingly unfocused fool. But after enduring the isolation of eco-anxiety and burnout, I now realize that Dad was right. Quitting a job where helplessness clings to you can open up space to focus on doing something about it. Kudos to those who can code and stick to it, but it took me years to learn that Python alone wouldn’t cut the cake 🍰. I wanted to move beyond the narrow focus of my old role, where sustainability was limited to lab optimization and study the causes of the problem itself —unsustainable energy use, addiction to growth, supply chain waste, and short-term business priorities, which needed broader solutions. I already knew I’d be better here, since being a systems thinker (which is just a professional way of saying full stack anxiety) and ‘feeling everything’ may make you restless in narrow specialisms—and, in hindsight, an impatient programmer—but it also drives you to leave no stone unturned and no one behind.

It is OK to not have the clearest picture of what comes next, and that you don’t need to know everything before you press escape. It doesn’t make you foolish, but smart enough to know what doesn’t work. Honestly, if I’d waited until everything was perfect, I’d still be at my desk, debugging in the dark, wondering if my unwashed hair could pass as a sustainability statement.

I also learned the power of shared experience when you are in the face-planting the boogy puddle of burnout. Sometimes, just one message 💌 from someone who was once a near stranger (in my case, Hana Walker-Brown) can change more than you know, even if it is making you feel less alone in your process of change.

Perhaps quitters aren’t people who give up—they are minds that have chosen themselves over an old narrative to better solve the problems they care about in a way they can. I can live with that, if anything, these people are needed more than ever.

Let me introduce to you to ‘The Pivot Hero’.

These are so good! so what’s your timeline. Are you planning on branding and doing other like minded artists into a collective coop that compliment each other services, do a documentary and the 4th book “the pivot”mid 2026? 😃2027 Get funding for expanding collective problem solving complimentary independent organization that expand outreach throughout community, using models and pilots in different cities. ?